Dropping Out of Dropping Out

When I Allowed Myself to Quit Quitting on Myself

Part I:

Friday afternoon, I finished finals week, and with that I have finished my five-and-a-half-year experiment in pursuing a higher education, beginning at community college and ending in a private university so renowned that parents around the world send their kids to Los Angeles to attend.

What makes it all the more remarkable to me is that when I was 17 years old, I dropped out of high school to get my GED.

After completely tanking high school, I then spent a year bumming around Queens, living off of my parents, hanging out with fellow layabouts who liked to drink and not hold down a job as much as I did, and generally lived that dirtbag life.

Then that got boring.

So at age 19 I started going to college at CUNY Queens College while also starting to perform standup comedy at open mics.

The following are three sentences that, in an ideal world, would be followed by a 3000 word story each:

1. At the age of 19, while starting my first semester of college, I also did my first standup set at a downtown black box theater during an “anything goes” performance art open mic.

2. Seven months later, I got booked for a comedy game show college tour where I managed to bomb at almost every stop.

3. Because of #2, I dropped out of college and never looked back.

I regret nothing. Truly. I’ve struggled more than some, because lack of a degree meant I couldn’t, for instance, get a meaningful day job at any company or through any temp agency that did extensive background checks.

I saw the inside of many call centers. If my early comedy work was dogged by an “I’m a loser” vibe that struck the audience as a little too self-deprecating, it’s because I believed it, and I believed that it was obvious to everyone else. My M.O. was to get ahead of it, to make fun of it before anyone else could.

And comedy gradually became a career. Which is not to say it can’t be glamorous, that it hasn’t had its share of once-in-a-lifetime experiences. There have been moments that have been so surreal that it felt like I’d stepped into someone else’s dream.

But it’s still a career, a string of jobs like any other, and your longevity is dependent entirely on how long, and how willing, you are to work harder than the next person to achieve it.

Part II:

I am graduating from a school known affectionately as the “University of Spoiled Children”, a world-class university with the best most celebrated film school on Earth. It is, also, a place where a lot of children of wealthy people attend.

My first year there was Sasha Obama’s final. This was supposed to be a big secret. It was not.

And yes, I saw her on campus once. I have a habit of looking strangers in the face; it’s a reaction to growing up in New York City at a time when the default was to look away or maybe get hurt.

We passed each other. She gave me a look like, “Yes you recognized me.” After she passed I realized who she was. I probably still have a jacket with the Secret Service.

That’s the kind of school it is.

Growing up in Queens, a working-class borough, I carried with me a deep skepticism toward the rich college kids who treated Manhattan like a playground—people who passed through our neighborhoods and lives without staying long enough to feel the consequences.

Here’s an entry I pulled from an old journal, from when I was young and drunkenly stumbling home on the subway every night.

I call this A City of Two Tales:

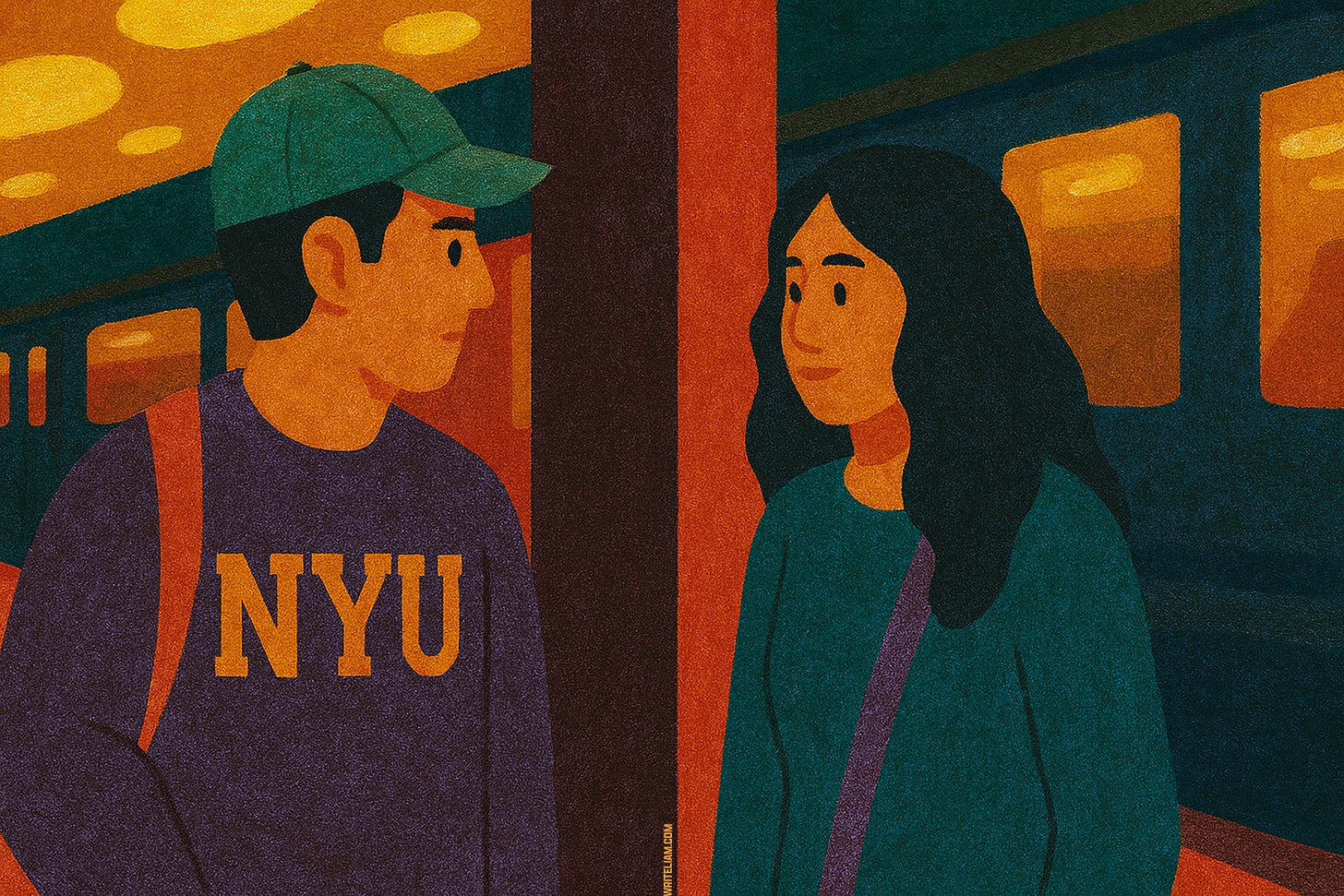

1. As I was waiting for the R train at the 8th street stop tonight, I overheard an NYU student discussing how much money he was getting from his parents (I swear I wasn’t eavesdropping, the kid was talking pretty loudly). This is verbatim what he said:

“I asked for $6,000 a month, because I figured I could live on five thousand and save a thousand in the bank. But it didn’t work out that way. I don’t know where it all goes...”

He then talked about how he feels bad lying to his parents about his financial needs but what’s he going to do? How he “only” has $3,000 in savings. Something about having to “withdraw from the fund.”

At this point, I’d moved down the platform. Luckily, his voice got a bit louder, so I could still listen to him complain about only having more money than most people I know.

I don’t know how his monologue ended, because that’s when the train came, and I had to throw him under it.

2. On my way home in Queens, walking down my street, I fell in behind a young man, same age as the NYU kid who was talking loudly and excitedly into his cell phone. Here’s what he was saying, verbatim:

“Yo son, you want to go to the spot? I got mad money. No, I - you know how you got thirty-five dollars and it’s not even food money and you can’t go nowhere? I got crazy money - I got - I got over three hundred dollars, so I got to go to the spot. No, I sell uptown. I go to school - “

That’s when I entered my destination and left him to walk on his merry way.

Part III:

When I got accepted three and a half years ago, I immediately felt the old weight of loserdom press upon me. I preemptively decided that a high school and college dropout, someone who was going to go on a full-ride scholarship no less, could never be truly be accepted by the highly-ambitious children of wealthy and successful people who are most likely my age.

So I said to my mom, “How am I going to not feel an incredible resentment towards all the rich kids around me?” Her answer was the best:

“Remember that their tuition is what’s paying for you to go.”

I have a lot more to say about my schooling experience, especially as an older adult who never fit in with his own peers let alone a younger generation. But for now I’ll leave with that wise piece of advice.

Thanks for reading.

This newsletter is where I write essays, stories, and comedy—about work, filmmaking, and learning how not to quit on yourself.

If that sounds like your kind of bag, you can subscribe for free.

PS: I always forget to mention this, but my stand-up special West Coasting is streaming. You can watch it here.

Your mom's comment really was the topper to a great post.