THE B-SIDE: Last Thoughts on David Lynch

On anxiety, illusion, and the long drive home

In 2025, I committed myself to rewatching every David Lynch movie, in order, at a theater that was playing them all on a large screen with state-of-the-art Dolby surround sound. That last detail was important, because more than the visuals, the acting, the costuming – as exact as Lynch was known to be on those points – Lynch placed an importance on sound design, to the extent that he involved himself heavily in it in post-production.

There’s a certain kind of film fan who will button-hole you and demand you respect Lynch’s importance. I’m not that kind. But I grew up in a time and place where an appreciation of action comedies (which I genuinely love) were normal, and an appreciation of art in cinema was suspicious. David Lynch made movies that were important to me as a human being who wanted to evolve.

Here, then, are some final thoughts on David Lynch and on some of the most important movies in his filmography.

ERASERHEAD (1977)

This was only my second time seeing Eraserhead—the first was when I was thirteen and spent my birthday money at J&R Music World on two VHS tapes: Eraserhead and Copacabana with Groucho Marx and Carmen Miranda.

Copacabana was unbelievably surreal in its own way – it was Groucho’s first significant starring role in a movie without his brothers, and he starred as a down-on-his-heels talent agent whose sole client and wife is the beautiful, glamorous Carmen Miranda. There are a lot of Carmen Miranda production numbers, and one featuring Groucho auditioning Groucho for the club.

I loved Copacabana - I watched Copacabana so many times it wore out the tape; Eraserhead I watched once and never touched again until this past year. Seeing it as an adult, I realize why that first encounter was so unsettling: the oppressive industrial drone, the black-and-white murk that feels damp to look at, Henry’s anxious silence, the sickly dinner scene with the twitching little chickens, and of course the infamous, fragile alien baby.

My parents always liked to watch along and check out whatever I was watching. My dad watched a lot of garbage on my account – he would sit and watch Full House and Mr. Belvedere every week with me, which I realize now as an adult was a pure act of love.

This time they were both out of the room in 5 minutes. I never quite stopped thinking about it, though. Seeing Eraserhead on the big screen and not on the little TV with bad mono sound for the first time was an education in escalating discomfort and curated anxiety. All of it felt like a bad dream you can’t wake up from—partly funny, mostly unbearable—and as a teenager I think I just sensed that it was about something I wasn’t ready to understand.

I liked Eraserhead, I just couldn’t rewatch it because anytime I went to buy a ticket an art house theater, or saw it in a video store I always got that feeling in my spine - dread, anxiety, the soundscape that dared you to keep watching. It brought me into a bigger, stranger world and as I grew into adulthood and sought out that same feeling in a moviegoing experience, I was disappointed to discover how singular Lynch – and in particular that debut film of his – were.

THE ELEPHANT MAN (1980)

Mel Brooks picked David Lynch out of a crowd of aspiring directors based (so he says, although everything Mel Brooks has to be taken with the understanding that he likes to throw out the truth in favor of the punchline) on believing Lynch was British.

Mel Brooks famously took his name off The Elephant Man, his drama about John Merrick, a real historical figure whose deformities isolated him from polite society, sidelined him into a career as an attraction in a second-rate sideshow, and earned him the titular nickname. Brooks wanted to produce this film as a prestige drama, and he knew that his name would signal to his fans that this was a wacky comedy.

Ultimately, it makes sense in hindsight that Brooks would hire Lynch based on the strength of Eraserhead; Lynch’s debut film is a confident slow-burn journey to the horrific and emotionally uncomfortable center of anxiety around relationships and fatherhood. Similarly, The Elephant Man needed a writer/director with the strength to explore Merrick’s innocent emotional center that belies the initial feel of horror one feels at seeing his face for the first time.

And because Brooks was in a position to serve as a mentor to Lynch, one watches Lynch make leaps and bounds in his progress as a filmmaker from his first movie to this. And yes, there are still strands of Mel Brooks DNA in this movie:

The medical college sequence with the first public unveiling of Merrick behind a backlit white screen was very similar to Brooks’ work in Young Frankenstein in the way that the camera moved, and also in the line the sequence walks between drama, horror, and finally deadpan comedy with the commentary on the normality of Merrick’s genitals. If Merrick had walked out singing ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’ it would have not been quite so surprising, although it would have made this a very different film.

By the time The Elephant Man had begun production, Brooks was not just a top tier comedian, he was a steady and accomplished filmmaker whose earliest work, dating back to The Producers and even his work writing on broadway, showed an ability to not just outrage or even horrify but tell a story with an eye towards appealing to the broadest audience possible.

In 1977 he released a Hitchcock pastiche, High Anxiety, which Hitchcock himself had had a heavy hand in helping Brooks put together. Working with Hitch certainly must have been an education as a filmmaker.

Which is not to say that The Elephant Man was ultimately a Mel Brooks movie (although the scene with the head nurse clonking the porter over the head, which is sentimental slapstick that could have come from any of Brooks’ looser efforts), but there is a marked shift from the abstract and dense symbolism of his earlier films, with a difficult visual aesthetic and an off-putting sound design, that is markedly toned down in this, only his second film.

While post-Dune Lynch comes into his own as a filmmaker and storyteller, he clearly had learned some lessons at Brooksfilms that ensured that his work found, if not the widest audience, a formidably large cult.

BLUE VELVET (1986)

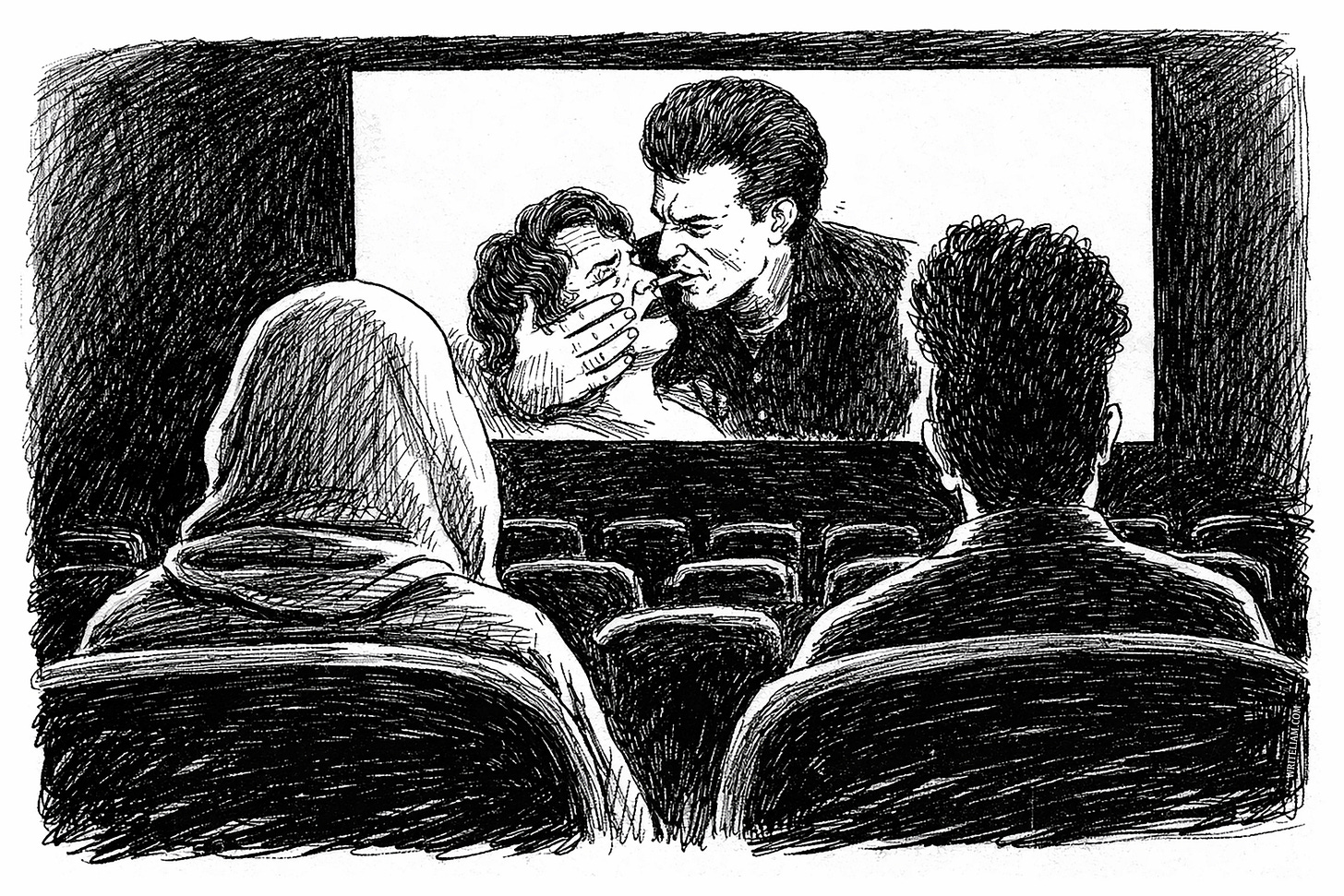

This was my third time watching Blue Velvet, but the first time I’ve seen it on a proper big screen—and I immediately regretted sitting in the front row. I’d always thought I knew the movie pretty well, but at that distance the colors and shadows felt almost too vivid, like the screen was pressing down on me. I actually couldn’t bring myself to watch the entire sequence where Jeffrey hides in Isabella Rossellini’s closet; I had to look away.

On a TV at home it plays as suspenseful and strange, but in a theater, up close, it feels like a matter of life and death—you’re not just worried Jeffrey might get caught, you’re convinced that if Frank Booth yanks that closet door open, he’ll kill you too. The combination of the stillness, the creaking hinges, and the heavy breathing makes the scene feel suffocating, as if the whole theater is holding its breath.

What’s worse—and what makes it so powerful—is that I felt implicated in Frank’s deranged assault on Rossellini’s character, like being forced to witness it made me complicit in the violence. It’s deeply upsetting, but that’s also what makes the filmmaking so brilliant: Lynch refuses to let you feel like a safe, detached observer.

MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2001)

This is my favorite Lynch movie, and that’s no surprise.

It’s the complete synthesis of everything David Lynch had been building towards with his work up to that point. There’s a lot of the tone and structure of Twin Peaks in the film’s DNA, and that’s probably because it began life as his fourth attempt at a television series. You can feel it most strongly in his subversion of old-fashioned film tropes: the plucky young ingénue making her way through Hollywood, the John Huston-style noir plot that starts with a beautiful amnesiac who’s more than she seems, the Auntie Mame–style older women who enter in and out of the story, offering guidance and clues.

But whereas the shiny chrome surface of Twin Peaks – with the coffee, the doughnuts, and the quirky townsfolk – provides a bright sheen that provides contrast with the darkness lying just underneath. In Mulholland Drive, the sunny tropes are the darkness. They’re not just a mystery; they’re the trap.

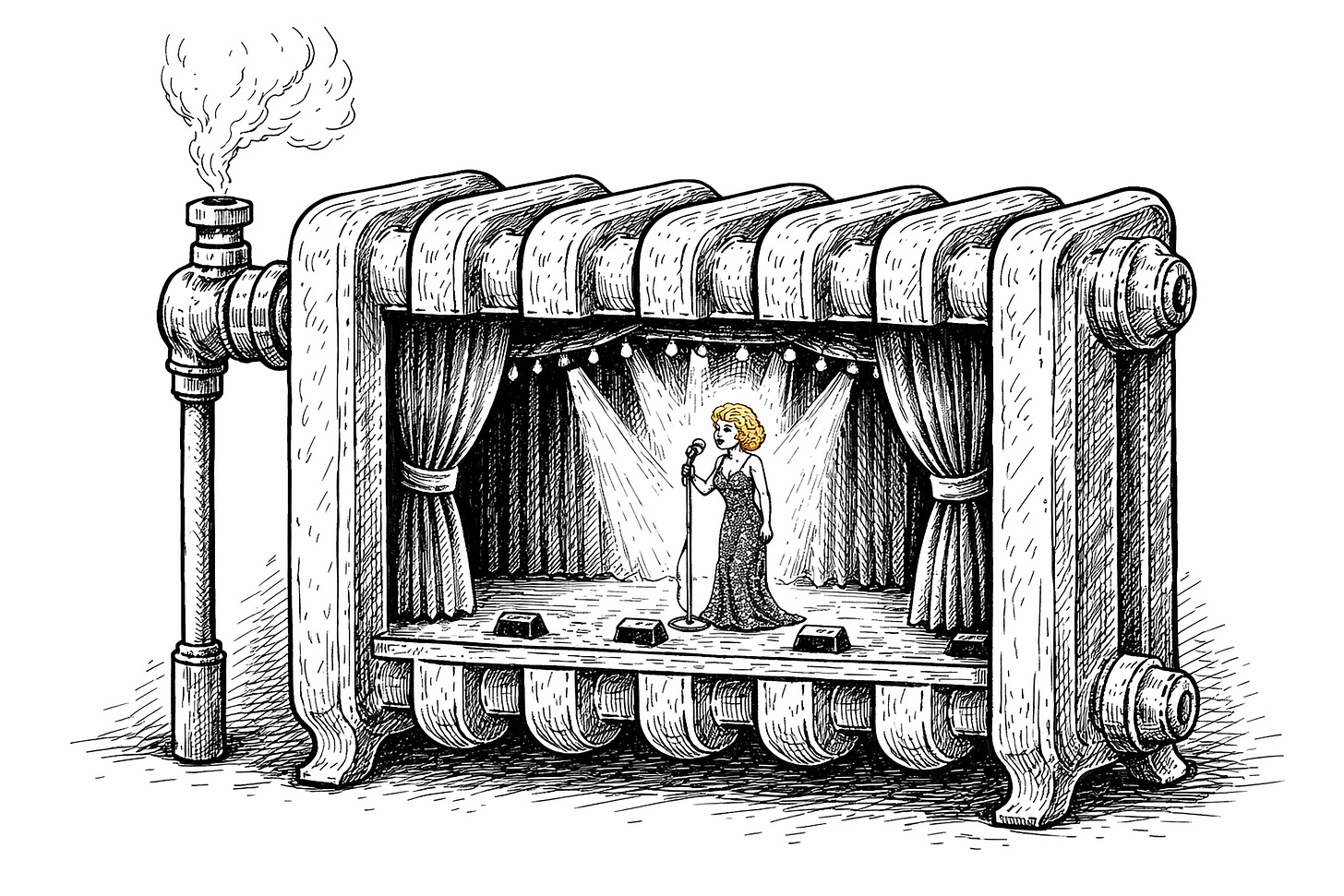

And by the time we reach the Club Silencio reveal, the solution to the mystery feels less like a relief than a complete betrayal. Because we’ve invested so completely in Betty’s gorgeous, fragile fantasy that seeing the machinery behind the illusion feels devastating. All of this is foreshadowed in the film’s most seemingly disconnected scene, the “Bum Behind Winkie’s” sequence that betrays the dark, rotten heart that beats within the shiny lie that is Hollywood.

THE STRAIGHT STORY (1999)

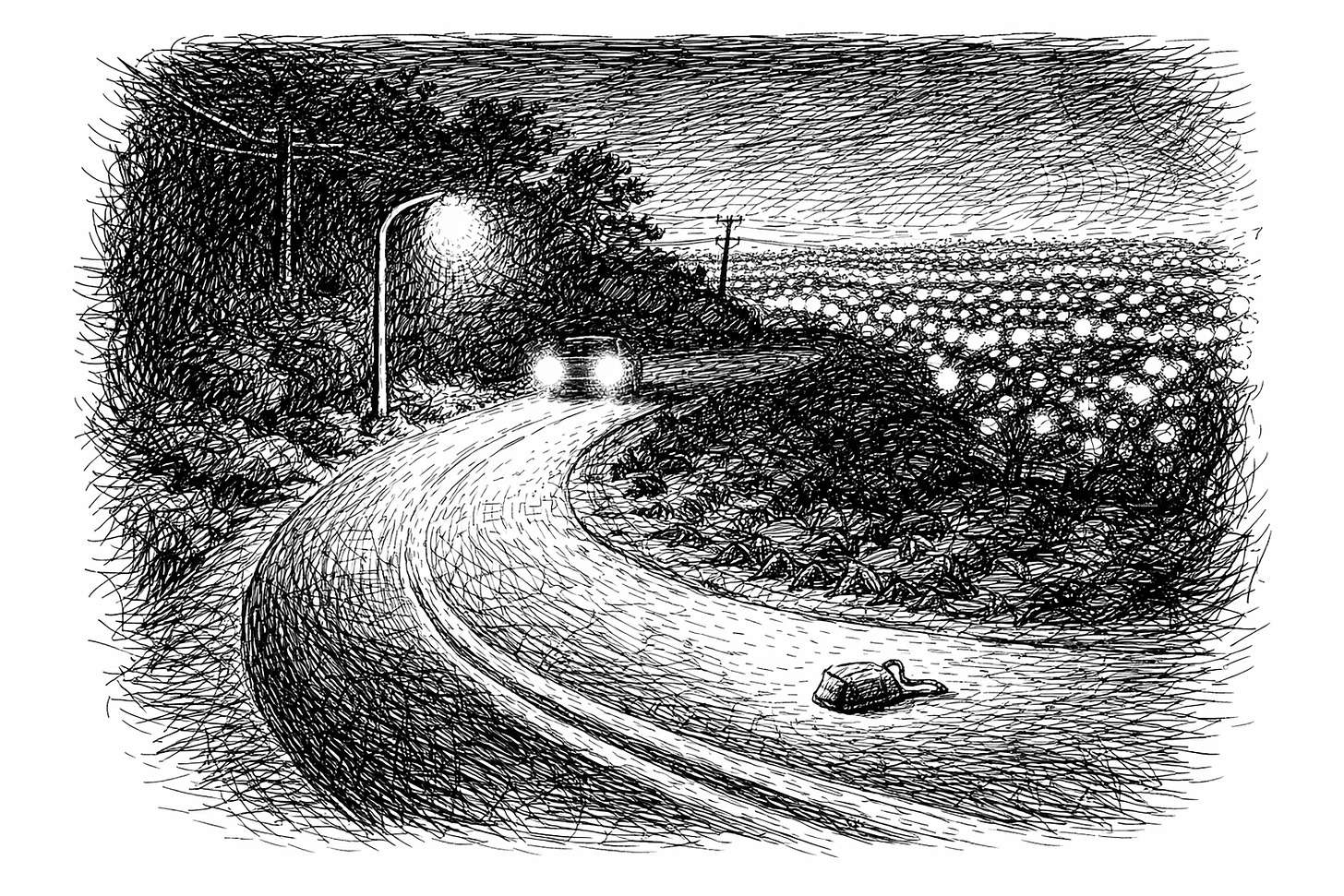

The first time I saw The Straight Story was opening weekend in a packed movie theater on 3rd Avenue, downtown Manhattan. The woman next to me kept taking calls on her phone, and this was early enough in the development of cell phone technology that we as an audience had no idea what to do about it, what the protocol around cell phones even was. The persistent ringing of that phone and the loud conversations that followed threw an element of noisy chaos into a movie that, uncharacteristically for Lynch, had none.

The third time I watched The Straight Story was in a park in Astoria, Queens, as part of a Movies Under the Stars program. My previous experience with the screening series was with The Great Muppet Caper, which involved a Parks employee pressing play on a DVD and screening the movie on a small screen that became clearer as the sun set. The park was filled with families, and as the Muppets sang and danced their way to Broadway the kids gradually exhausted themselves running around, screaming, playing, being children.

The Straight Story, on the other hand, was a completely different experience. If Lynch takes a maximalist approach to violence, suspense, and sex in his previous works, my experience watching The Straight Story is more akin to the concert of minimalist composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass I attended at BAM in 2014. The quiet, the repetition, the understanding of the spaces where notes and beats are supposed to go but refusing to fill them, all of these create a hypnotic effect that drag the audience in.

If Frank Booth is the ultimate exemplar of evil excess, Richard Farnsworth’s Alvin Straight is quiet human decency personified.

Even outdoors in Astoria Park, this movie worked. The kids quieted down instantly and closely followed the most “un-Disney” plot conceived - an old man on a tractor driving, failing, and driving again to meet with his dying brother. Nobody made noise but the babies, nobody left until it was over.

I publish here every Monday and Thursday — essays like this, along with comedy, sketches, and bits of literary memoir. If this piece worked for you, you can subscribe below to get new posts in your inbox.