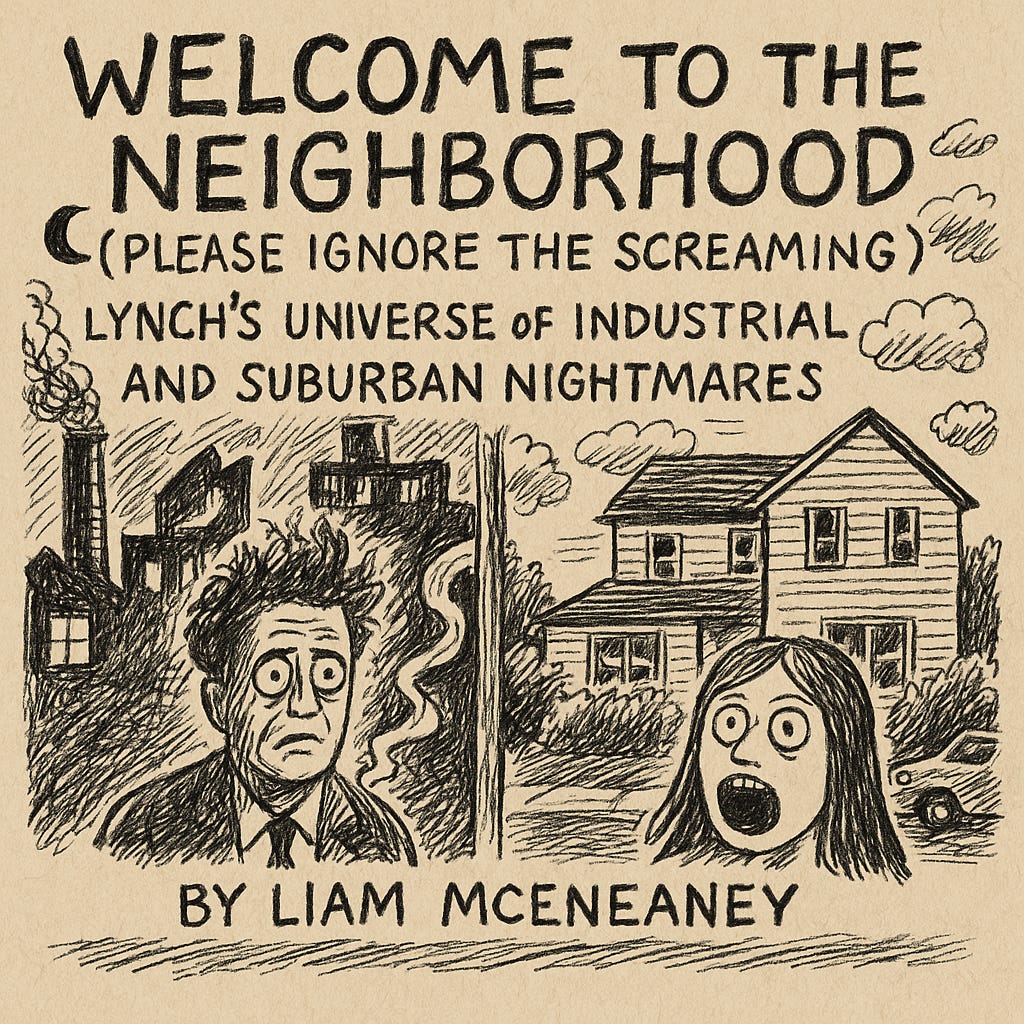

THE B-SIDE: Welcome to the Neighborhood (Please Ignore the Screaming)

David Lynch’s Universe of Industrial and Suburban Nightmares

David Lynch is one of those rare directors who can make you feel an unbearable sense of dread before anyone even says a line. The rooms do most of the talking; the quiet and the air do the rest. Take a look at Mulholland Drive – the famous diner scene (which I investigated in a previous essay) creates an unbearable sense of tension and suspense with a combination of one man describing his dream to another, and a lack of atmospheric sound design. It’s Lynch’s whole thing in miniature: he can make a room feel dangerous before anything actually happens.

If you like these film deep-dives, consider subscribing. I write about movies, storytelling, and the weird mechanics of human emotion every week.

In his early films—Eraserhead and The Elephant Man—you get these worlds that look like the neighborhood around a factory that has been running nonstop for about fifty years. Everything feels damp and mechanical and vaguely unsafe, like OSHA never existed, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere of oppression. Later, in Blue Velvet and Fire Walk With Me, the backgrounds get swapped out for lawns, diners, and that very specific “nice town where something terrible is obviously happening” vibe. What’s funny is that the rot never really changes. Lynch just moves it around the map. Industrial settings make the misery loud and in your face; suburban settings bury it under a smile and a plate of pancakes. Either way, the psychic mold keeps growing, and Lynch keeps pointing at it like, “See? Told you.”

In his industrial films, the environment feels like it has a grudge. In Eraserhead, Henry walks around like a man who wandered into The Twilight Zone, got a haircut, and was just too polite to say anything. The hallways go on forever, the pipes hiss like wild animals guarding a lair, and the aural environment feels hostile, deliberately designed to stress audience and characters alike. His apartment looks like the staging area for a panic attack. While The Elephant Man is slightly more grounded in reality, it’s not any gentler. Victorian London is basically a giant, smoke-belching machine that happens to have a population living in various degrees of discomfort. Soot lands on everyone like it’s part of the dress code. The environment doesn’t just set the mood—it actually feels like the cause of the mood. These are worlds where humans are smaller than the machinery running their lives.

One of the reasons the industrial settings feel so suffocating is that Lynch keeps erasing the boundary between people and machines. In Eraserhead, the baby doesn’t just cry; it wheezes like a broken appliance. It’s biological, it’s mechanical. In The Elephant Man, people treat John Merrick like he’s a defective product the factory shouldn’t have let out the door. Even the dream sequences mix the imagery of elephants with industrial noise, as if evolution and the Industrial Revolution shook hands and decided to ruin this one man’s life. In both films, the rot is environmental. You don’t have to dig deep for it; it’s right there in the air, in the walls, in the sound design. The world breaks you long before you get the chance to break yourself.

Then Lynch shifts to suburbia, and everything gets creepier precisely because everything looks normal. Blue Velvet opens like a 1970s parody version of Norman Rockwell’s 1950s America. A spotless lawn. A smiling guy watering it. A fireman waving from a truck like he’s been training for this moment. Then the camera goes underground and suddenly there are bugs everywhere, chewing away at the roots. It’s Lynch screaming aloud what his previous work had whispered; the rot was here the whole time; you just weren’t invited to look at it.

When Jeffrey finds the ear, it feels like the town’s own subconscious accidentally dropped something incriminating on the sidewalk. The scary part isn’t that evil exists—every American town has a Frank Booth hiding somewhere. The scary part is the way the town keeps smiling through it. Suburbia, in Lynch’s hands, is a place where denial is basically a zoning requirement.

If this kind of analysis is your thing, I write pieces like this regularly. If you want more deep dives on film and storytelling, subscribing is the easiest way to keep up.

Fire Walk With Me takes that whole idea and drops it on Laura Palmer like an anvil. The town of Twin Peaks that America fell in love with isn’t just aggressively cute—it oftentimes borders on twee. Everyone knows everyone, and everyone acts like they’re starring in a coffee commercial. Meanwhile, Laura is carrying enough trauma to power a small horror franchise, and nobody wants to actually see it. She smiles because that’s the role, and the town applauds her for sticking to the script. Inside the Palmer house, though, the walls feel tight, the lighting feels wrong, and you can tell immediately that something terrible is happening just out of frame. The violence and grief don’t leak into the environment the way they do in Eraserhead; they bounce around inside Laura until there’s nowhere left for them to go. By the time we get to her actual murder, it almost feels like a relief to see the end of her suffering. Which is ultimately, the true horror that fuels the entire Twin Peaks experiment.

When you line these films up, you see that Lynch isn’t really changing his interests—he’s just changing the way in which he explores them. The industrial backgrounds in these movies take the corruption that is normally obscured and makes it obvious – much like the Bum Living in the Dumpster behind Winkie’s. Everything is dirty, crumbling, overheated, or leaking. The characters look like they need a long shower and a union rep. In the suburban movies, the corruption hides behind birthday parties, school events, and those weirdly formal living rooms no one actually sits in. But the same tension runs through all of them: people who feel trapped by a world that refuses to admit something is wrong. Industrial rot is environmental; suburban rot is psychological. The first hits you in the face, the second gets into your bloodstream. But emotionally, they land in the same place.

This is where The Straight Story becomes interesting, almost like Lynch decided to run a little experiment: “What happens if I take the rot out entirely?” It’s easily his nicest movie—sunlight, kind strangers, wide open spaces, no sinister subplots hiding behind the cornfields. But it still feels like a Lynch movie; in fact it’s a Lynch film with a kind of emotional synesthesia — the senses he normally assaults get rerouted into quieter channels.

The landscapes are calm, but they’re also huge in a way that makes you think about everything Alvin Straight hasn’t dealt with. The fields and the long highways don’t feel evil, but they do feel honest, which might be harder to face. When the environment stops doing the heavy lifting, the emotional weight shifts entirely onto the character. The rot doesn’t disappear; it just stops being atmospheric and becomes personal. It’s like Lynch asking, “Okay, what do you do when the world isn’t hurting you and it’s just your own life catching up?”

What keeps Lynch bouncing between factories, suburbs, and long stretches of Midwestern road is his fascination with the gap between what a place looks like and what it does to the people living in it. Industrial spaces say the quiet part loud. Suburbs say the loud part quiet. And The Straight Story—weirdly enough—says almost nothing at all, which forces you to sit with the stuff you were trying to avoid. While this is implicit for the most part, it becomes explicit at the end when Alvin finally reaches his brother (played by the sublime Harry Dean Stanton) and the two men say almost nothing at all.

In the industrial films, the environment is a bully. In the suburban films, the environment is an accomplice pretending to be innocent. In his rural film, the environment steps back and lets your life interrogate you. Different settings, same emotional mission: show people trying to hold it together inside a world that won’t meet them halfway.

In the end, whether Lynch is filming a nightmare factory, a cheerful cul-de-sac, or one very determined man on a lawnmower, he’s always circling the same idea: pressure. External pressure, internal pressure, emotional pressure that builds until the character cracks in some way they can’t hide anymore. Industrial worlds make the pressure visible; suburban worlds smother it under nice furniture; rural worlds leave you alone with it. But it’s all the same story. People carrying around their private darkness and trying—sometimes failing—to find a place where the world will let them put it down for a second. Lynch changes the setting, but not the struggle. The rot moves, but it never actually leaves.

If this essay resonated with you, consider subscribing for free. You’ll get new essays every week, plus updates on my writing and projects.

Your reads and shares genuinely help this newsletter grow.