The Balcony and the Spotlight

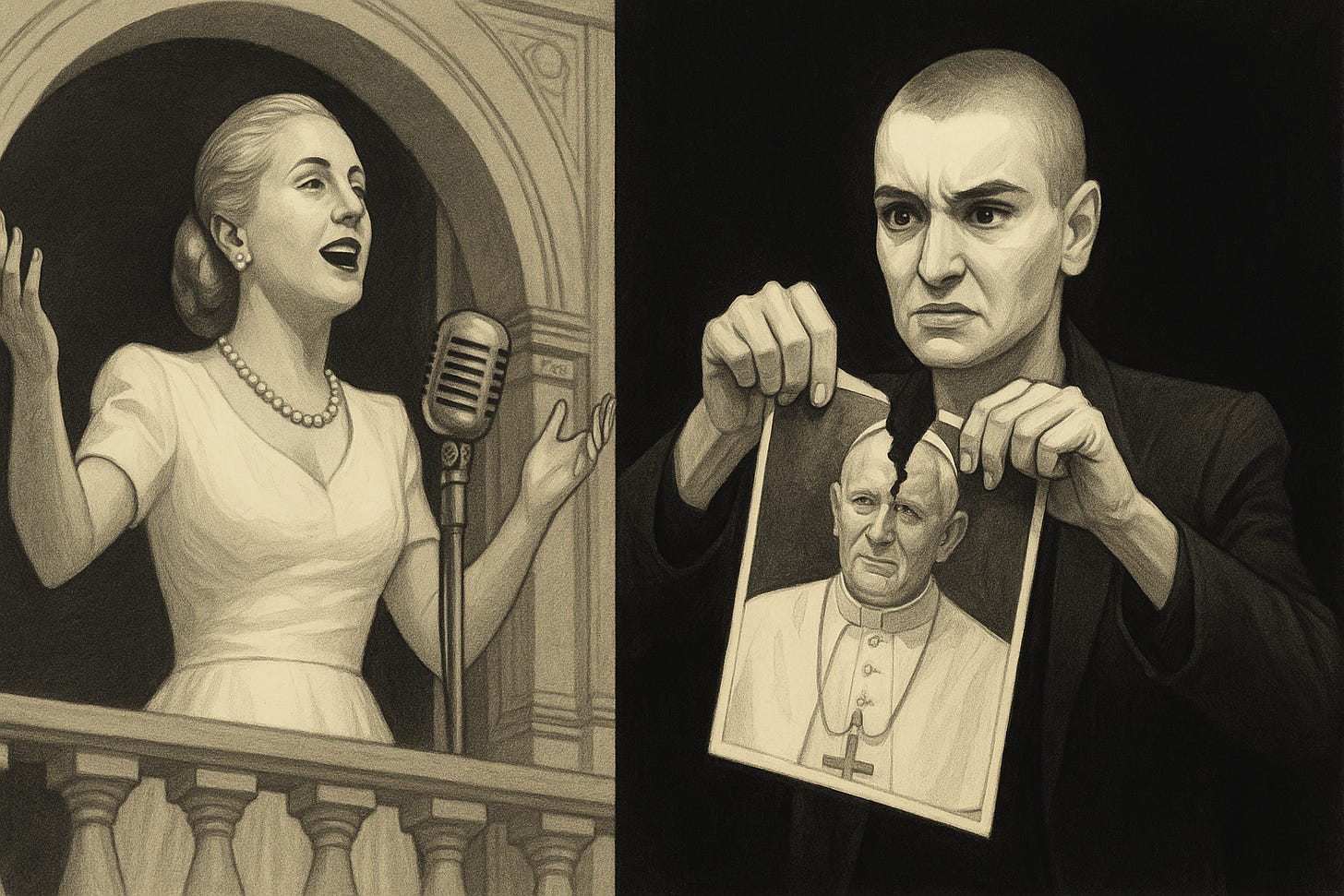

Eva Perón’s myth was immortalized in Evita. Sinéad O’Connor, in a fragile, devastating cover of its signature ballad, revealed the personal cost of speaking truth before the world was ready to hear it

On one stage, a woman promised to carry her nation; on another stage, another woman tore at the silence of an institution. Both sang, both burned brightly, and both paid dearly. What remains is a song—part anthem, part elegy—that holds their stories in tension.

It’s an odd fact that Eva Perón, beloved wife of Argentine dictator Juan Peron, got a Broadway rock opera and Sinéad O’Connor has yet to. Both women lived high profile lives, both carried their private pain into the public square, and both became lightning rods for their countries’ hopes and rage. One sings from the balcony of the Casa Rosada and promised to carry her people with her, the other tears up a photo on live TV in the hope that she could affect change in a corrupt institution that profited from misery — and in both moments, they turned their voices into weapons.

Eva Perón’s life was so fantastic, and her following in her home country of Argentina and abroad still as outsized as her personality by the time she succumbed to cervical cancer in 1952, that it seems unlikely that of all the adaptations of her life story in book, film, and stage—including a made-for-TV biopic starring Faye Dunaway as Eva—only the musical would take a prominent place in the pop culture pantheon.

It's not an exaggeration to say that Perón lived a real-life fairy tale; having been raised in poverty after her wealthy father abandoned her family, she willed herself into reinvention several times. First as a successful actress, then the wealthy wife of a powerful strongman, and finally as an immortal international symbol of the dreams of the humblest of the Argentinian people.

That’s not an exaggeration. When Argentina emerged from its postwar isolationism and joined the United Nations, Perón embarked upon an international tour meeting the heads of state of the nations of Europe, starting with brutal Spanish strongman and Chevy Chase punchline General Francisco Franco.

The more I’ve read about Sinead O’Connor’s life, the more I realized that fact that her life hasn’t been made into a Broadway musical speaks more to a failure of imagination among the creative elite of “The Avenue" creative elite than it does to Sinead’s talent or her effect on the world. Indeed, her biography reads like exactly the kind of tragicomic rags-to-riches-to-reviled fairy tale that makes for high drama in low art. It’s a redemption story that ends as the world realizes that everything she’d preached from the stage was—as painful as the powerful might find it to admit—correct.

Born into an abusive household (which also produced her brother, the award-winning novelist Joseph O’Connor), she was put into the care of the Sisters of the Order of Our Lady of Charity at age 15.

That year she also sat in on her first professional recording session, and by age 21 she was an international pop star after the release of her first album, The Lion and the Cobra. As her star rose, so did her compulsion to use her position to help bring attention to various issues including sexual abuse among the poor and defenseless within the Catholic Church, a full decade before the public was ready to start hearing survivor’s stories.

The more famous Sinead got, the more publicly vulnerable she became, the more emotionally naked her public appearances, the more raw her pleas for help for herself, for others. More about this later.

I’ve never been a huge fan of the show Evita. The score always felt typical of Broadway’s Pewter Age excesses, with a little bit of everything thrown in – rock, opera, disco. Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, in recounting the life and public career of Eva Perón, created a show that has remained a mainstay in the pop culture collective conscious for one reason and one reason only: in the middle of everything is an absolute banger of a ballad (which is technically a reprise), “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.”

Opening the second act, the ballad is sung by Eva Perón on the balcony of the Presidential Palace on the 1946 evening that her husband, Juan, is elected President of Argentina. Eva sings about her renunciation of her dreams for wealth and fame in favor of service for the people of Argentina. The show’s Jiminy Cricket—the conscience on Peron’s shoulder and true voice of The People—is Che Guevara who provides an ironic counterpoint in commentary.

But this moment belongs to Evita, and more to the point, the mezzo-soprano playing her. Patti Lupone in the original Broadway production (with Mandy Patinkin!) plays this as a dramatic pronouncement. Indeed, in most productions this becomes a showcase for the actress’ vocal range. In fact, Lupone’s interpretation on the Broadway soundtrack sets the standard for American performances of the role, allowing her voice to build and build until the final refrain of “Don’t cry for me, Argentina, the truth is I never left you” positively soars.

It's Elaine Page, in creating the role in the original production on London’s West End, who adds the dramatic layers to her performance of the song. Below is an appearance Page made on a British chat show in 1980, while the original production of Evita was still running. Here we see a lack sentimentality or showcasing, an absence of the kind of showboating later artists would exhibit when tackling the song. Her Evita is by turns performatively open, cynical, and finally guarded and dismissive. This performance is less of a lament and more of a politician putting on a performance of lamenting:

Where Perón’s balcony scene staged power as performance, Sinead O’Connor’s stage moments revealed the cost of refusing to play along. To say that 1992 was an eventful year for Sinead would be an understatement akin to describing Fall, 2001, as a period of urban renewal for downtown Manhattan.

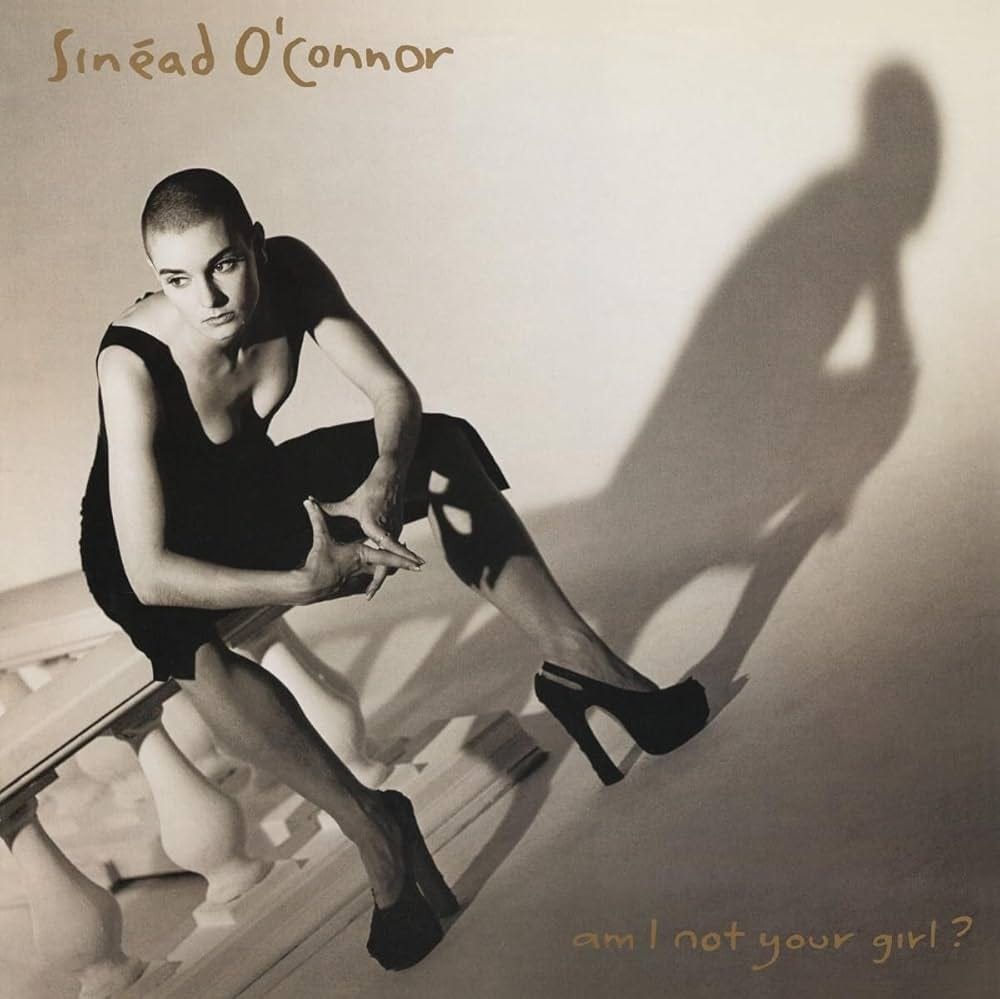

On the back of the massive success of her second album, 1991’s I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got - the one with “Nothing Compares 2 U” – she entered September of ’92 with am i not your girl?, an album of standards from the Great American Songbook.

In this collection, Peggy Lee’s 1929 Kalmar/Ruby-penned hit “Why Don’t You Do Right?” from Stage Door Canteen rubbed shoulders with Loretta Lynn’s classic lament “Success Has Made a Failure of Home.” She’s backed by a big jazzy band on some tracks and a huge swelling orchestra on others. Sometimes it feels like she’s fighting to be heard on her own album.

It was during a performance promoting this record in an October appearance on Saturday Night Live that she famously tore up a picture of the Pope, a career-defining act of protest following an a cappella rendition of Bob Marley’s song War whose lyrics were taken almost verbatim from a speech by Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I before the Eighteenth Session of UN General Assembly. (Selassie is considered a God in the Rastafarian religion. It’s a very interesting – and not in any way funny! – fact.)

This performance forever changed the course of Sinead O’Connor’s life, and allowed her enemies and rivals to smear her with the “crazy” label whenever she emerged in public life.

And yet, tucked into that same album—overshadowed by scandal—was her cover of the very song that had made Evita immortal. In the middle of this album, in the middle of this whirlwind of emotional chaos, is perhaps my favorite cover of ‘Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.’

Whereas Page’s original was guarded and ultimately disdainful, where LuPone’s version is soaring and operatic, Sinead O’Connor takes the song and turns it inside out. She makes it an incredibly personal and sad lament about the effects of catching the dreams you were chasing, about seeing the price of fame and fortune.

It sounds like the suicide note for a career.

“It won’t be easy, you’ll think it’s strange, when I try to explain how I feel that I still need your love after all that I’ve done.” This is how it opens, and O’Connor sings it with a fragility and a weakness belied by the strength of her voice. This isn’t an address to a loving nation, this is a plea to her fans for understanding, to a friend for comfort, to a lover for forgiveness.

I won’t go through this song line-by-line explicating its various changes in tone and mood – it’s better to listen on your own and discover it for yourself – but by the mid-point, “And as for fortune, and as for fame, I never invited them in” when she really punches the lyric, “they’re not the solutions they promise to be”, you get the sense that unlike Peron’s alternating turns of confession and jaded disconnect in the musical, O’Connor sounds like she’s explaining that this is a lesson she’s discovered the hard way.

In the end, Evita’s Eva sings this song as a culmination of triumph, as the victory song that comes midway through her story before learning that there’s a downside to getting everything you want. Whereas Sinead sounds like she’s giving a valedictory; that she’s found that her world is hollow and she has touched the sky, that she’s ready to give up the madness that comes with being a wealthy celebrity.

If that was the case, then she certainly chose a fantastic way out. In tearing up the Pope’s picture as a protest against what we now know to be the Catholic Church’s long history of exploiting children for sexual purposes, she also made this song a quiet farewell, a recognition of the cost of carrying too much truth in a world unwilling to hear it.

She remained hugely famous, of course. But she famously got booed a couple of months later at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at Madison Square Garden - tens of thousands of Dylan fans who had been grooving along to his famous protests songs like “Blowing in the Wind” and “The Times They Are A’Changing” - with only Kris Kristofferson coming out to offer moral support.

If Evita’s balcony scene became a monument to ambition made immortal, Sinéad’s interpretation feels more like a candle flickering against the wind—fragile, unguarded, but impossibly luminous while it lasted. Broadway may never give her the grand staging she deserves, but in that trembling, heart-rending cover, she wrote her own requiem in a cover of an Andrew Lloyd Webber showtune: not a plea for applause, but a benediction whispered to anyone who has ever felt both chosen and forsaken.

Sinéad’s voice still echoes, fragile and unyielding. If you’d like to hear more stories that braid together history, culture, and memory, consider subscribing — it’s the best way to keep the conversation going.