BONUS: Zadie Smith, Goodfellas, and the Queens of My Childhood

I Grew Up Near the Lufthansa Heist. I Thought Everyone Did.

To my subscribers: I wasn’t planning to send five emails in a week. I genuinely apologize. But novelist Zadie Smith wrote a beautiful essay for Galerie about Goodfellas, and it hit me right in the childhood. I grew up in Rego Park, not far from where the real Lufthansa heist guys hung out, and I had some thoughts.

So consider this a bonus post: part film analysis, part Queens kid remembering where the bodies were buried - underneath the floor at Robert's Lounge, 114-45 Lefferts Boulevard in South Ozone Park - and part Proustian dive into literary memoir.

Yes, I used the word “literary”, because I’m engaging with a real novelist and I also write real good. See? Bonus means it’s good, not annoying.

(If you somehow still don’t own Goodfellas, you can fix that here. That’s an affiliate link so I do make money if you click on it.)

In Smith’s piece she shared that Goodfellas is her favorite movie, which was surprising, possibly intentionally so, for someone whose byline appears in The New York Review of Books. It’s worth a read as it thoughtfully explores the film’s themes of morality, performance, and the seductive illusion of civility in a world built on violence.

I grew up in Rego Park, Queens, an oasis of calm and safety in the turbulence that was 1980s and 1990s New York City. It skewed mostly towards families and retired people. It was also adjacent to a lot of the neighborhoods where the action in Goodfellas took place – the real Morrie’s Wig Shop (a front for gambling) and Henry’s club The Suite were both a couple miles down Queens Boulevard into the grey area between Forest Hills and Kew Gardens.

Zadie Smith’s favorite scene is a second-favorite for many of my friends. Henry has the body of Billy Batts in his trunk, and they stop at Tommy’s (played by Joe Pesci) mom’s house to borrow a butcher knife to carve up the body. This is the famous scene where Catherine Scorsese steals the movie from three great actors by telling a humble joke and showing off a painting. All the while Billy is tapping on the lid of the trunk for help, to be let out, to let the world know he isn’t quite dead.

And that’s a great scene. But if you ask my friends, the scene is the one that comes right before it; Billy Batts, a made man, untouchable in the world of the New York mob, is having a sad little homecoming celebration at Henry’s club. He decides to bust Tommy’s chops, reminiscing about when Tommy was a shoeshine boy. “Get your shine box!” is something that any man my age will recognize as an off-hand insult.

Goodfellas is set in the Queens where I grew up, and it’s peopled by characters I recognize and locations that make me nostalgic for a New York City that no longer exists. Scorsese has a way of making it all feel glamorous, but as someone on the ground I can feel how grimy it was.

The dirty bars at night that stank so strongly of stale beer and staler cigarettes that the smell would dominate the sidewalk outside of an open tavern door. The pale men who hung out outside the OTB on Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills during the day, smelling of cheap cigars bought at the TeAmo smoke shop across the way. The dress shop that had the same ugly clothes in the front window year-after-year for decades and never went out of business.

That Queens, the world of Henry Hill, was a haven for the small-timers and the guys who never quite were.

The things you see and the things you hear when you’re a small child come to you without understanding context. When I was a child, there were a few things about the other side of Queens that adults joked about around me, not thinking I’d really be listening or absorbing what they said. So for a long time, I thought everybody knew about the Lufthansa Heist – if it was an in-joke in my world, according to kid logic, then it’s an in-joke in everybody’s.

There was an old man named Joe, retired, spending every halfway decent sunny day with the other old folks sitting in the benches in the back courtyard gossiping. His uniform was always a tan jacket with red or blue piping and sporty striped pants. Judging by my memory of his accent, he could have been Czech, or possibly Polish. When his wife passed, he was sad and slowly he regained the cheer with which he would greet anyone he knew.

One of his favorite jokes revolved around this fact: since my birthday falls on August 1st, and his on August 2nd, he would greet me in the summer months shouting, “Liam! You are one day older from me!” The building seemed to shrink and empty when Joe died, and I soon passed on to adolescent pursuits.

My dad told us about six years ago that before Joe retired, he had been a shylock – collecting money for bookies. There he was, a friendly old man, much like Henry surviving into his old age, because much like Henry—and a great deal of Scorsese’s best characters—he was ultimately a middleman.

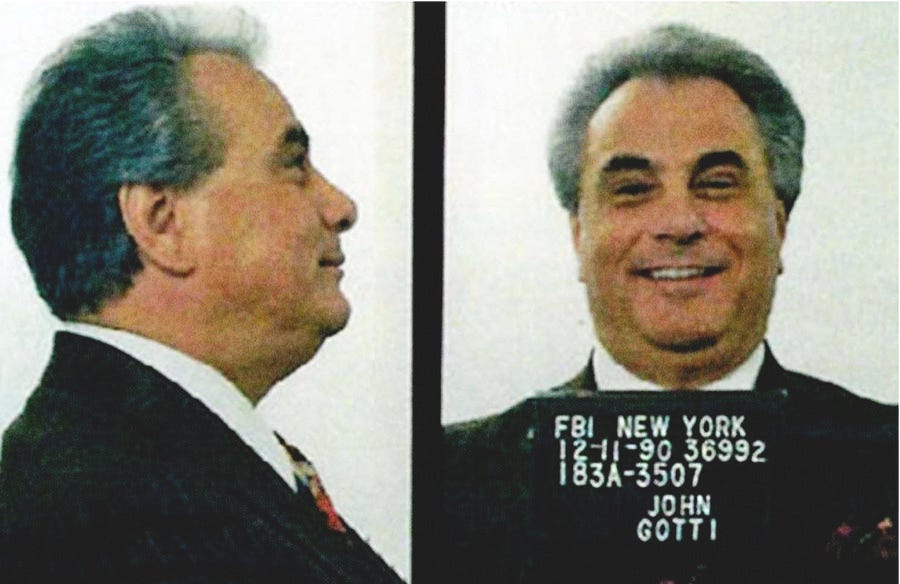

In one of Henry’s voiceovers, he describes the hoodlums he ran with as a kid as being just regular neighborhood guys who wanted to provide for their families. Indeed, the ultimate neighborhood guy was John Gotti lived in Queens, in Ozone Park. Gotti was a folk hero to many people I knew growing up because he took care of his family, he took care of his neighborhood, and whatever else he did wrong he beat the charges every time.

The fact that he built his empire on pain and death was secondary to the tertiary thrill felt by the common guy busting his hump, getting harassed by cops, getting berated by street-level bureaucrats behind the counter at the DMV, getting his pocket picked by the IRS.

For that guy, who didn’t know any of the people that Gotti put the hurt on, who could go to sleep at night assured that anyone killed by Gotti’s crew probably deserved it, Gotti got back for the little guy. Plus he put on massive fireworks shows when the Giuliani administration banned - and aggressively enforced — Fourth of July displays.

One of Scorsese’s favorite recurring motifs is the idea of the fall of man from a state of grace, especially once he has made the decision to commit an immoral act. And one of his recurring themes, starting all the way back in Boxcar Bertha, is that there is a state of, well maybe there’s a term for the Satanic ideal of a state of grace, where his characters who live between worlds without being accountable to either share a rarified life of luxury for which the price seems to always be paid by another person.

In Casino, DeNiro’s Ace Rothstein is a gambler promoted to the manager of the Tangiers casino, and the ensuing scenes of business-as-usual play (as most Scorsese movies do) as a sprightly comedy. But the price is paid in flesh and blood by his long-time friend Nicky whose job is to do all the violence and enforcement that Ace is too squeamish to handle himself. While Rothstein lives his life in the middle, neither mobster nor straight businessman, he’s safe.

It's once he makes the decision to choose the life of a legit businessman, to betray Nicky, to try to cage his wife, and to fight the bosses in the state government fairly - in other words to turn his back on his own nature in his pursuit of money and fame - that he finds himself punished and having everything he thought he loved stripped away.

In real life, if you read the book Wiseguy that the movie was lifted from almost word-for-word, Henry Hill wasn’t really a gangster. You don’t get a sense of it from the movie, but he was a neighborhood guy who everybody knew and liked, especially since the real-life Mob underboss treated him like family. He was less of an almost-a-made guy and more of a local fixer. He could hook you up with pretty much anything or anyone in his world, and he made his living taking percentages and running small deals of his own.

Not that Goodfellas elides that part of Henry’s life. After all, just like in real life, he survived the post-Lufthansa massacre by being content with whatever small fee he was paid to put people together, keeping his mouth shut, and being liked by Jimmy The Gent, the real-life counterpart to DeNiro’s character in the film.

But Henry was central to very little of his own life story; when he stops reacting to the chaos around him and makes active decisions, that’s when the life threatens to swallow him whole.

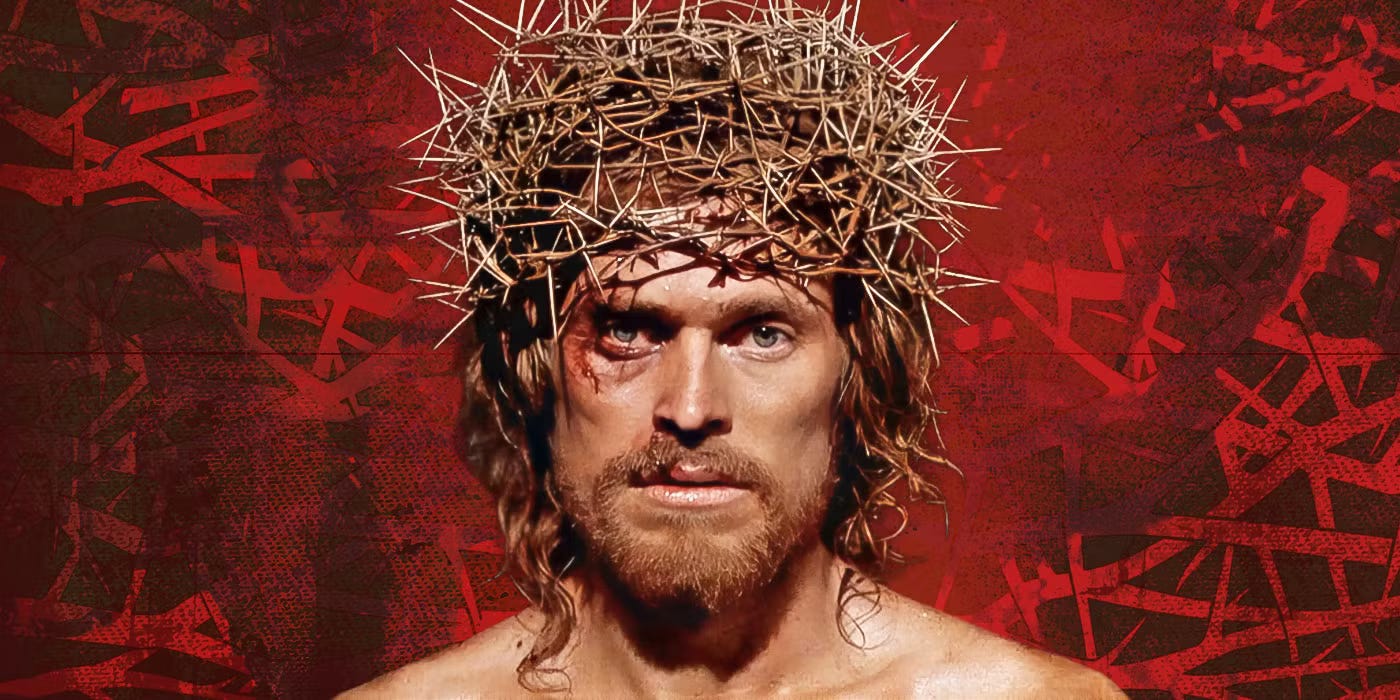

Scorsese doesn’t reserve this moral fall for gangsters. In The Last Temptation of Christ, even Jesus - the ultimate protagonist for nice little Catholic boy Marty - is tempted by Satan on the Cross, visiting him with visions not of wealth or fame, but of a long humble life where he’s married, has kids, and dies a peaceful death surrounded by loved ones.

It’s only when Jesus rejects this temptation, gives in to his destiny as a martyr and chooses to die for the sake of humanity that he is returned to his long, slow, excruciating state of heavenly bliss. Even Christ, in Scorsese’s telling, becomes a kind of middleman between mankind and the Lord.

It’s only when Henry makes that active second act choice to start dealing drugs against Pauly’s wishes that everything falls apart for him, that he loses what he treasures the most – his position in that world.

And so yes, the thing that draws the audience is escaping into the lawless world of whatever the opposite of divine grace is, where doing the wrong thing, making the wrong choices, committing the horrific acts of violence that our animal nature says we must while the pressures of our civilized nature tell us we must never do.

But what keeps us is the most relatable story – a guy caught in the middle, unable to claim authorship of his own life story, trapped between what he wants and what’s most prudent, and how he gets destroyed whenever he makes the wrong choice.

If you enjoyed this piece, do me a favor:

Share it with a friend, subscribe if you haven’t yet—and don’t worry, I won’t send Paulie to collect. Just promise you won’t sell that stuff now that you’re back out, alright?

P.S. You can unsubscribe at the same link if this is too much. I get it. Not everybody wants five emails and a Lufthansa reference in one week.